Record high of 6.6 million hires per month, above pre-pandemic record 6.0M.

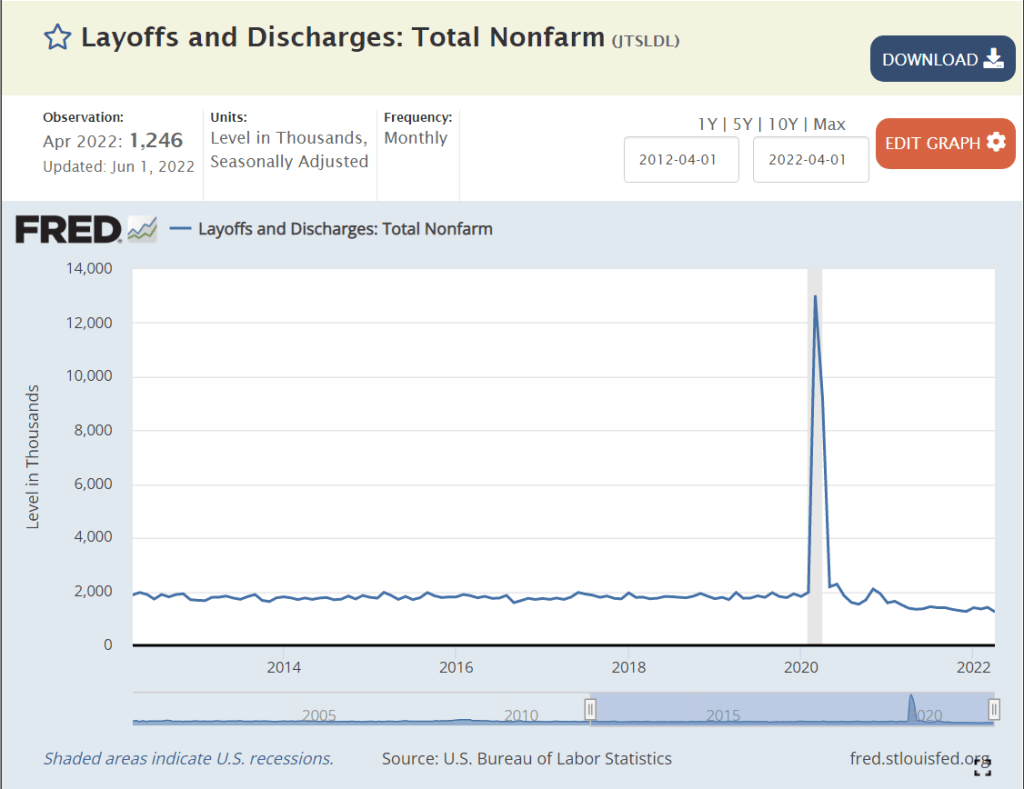

Record low layoffs at 1.3M per month, down from 1.8M pre-pandemic record. Yes 5 new hires for every layoff!

Record 11 million plus, up from pre-pandemic record of 7 million.

Record 7% of jobs are open, far above pre-pandemic 4.4% record level.

Job seekers to open positions ratio is less than 1/2, all-time record low, down from pre-pandemic record that was just below 1:1.

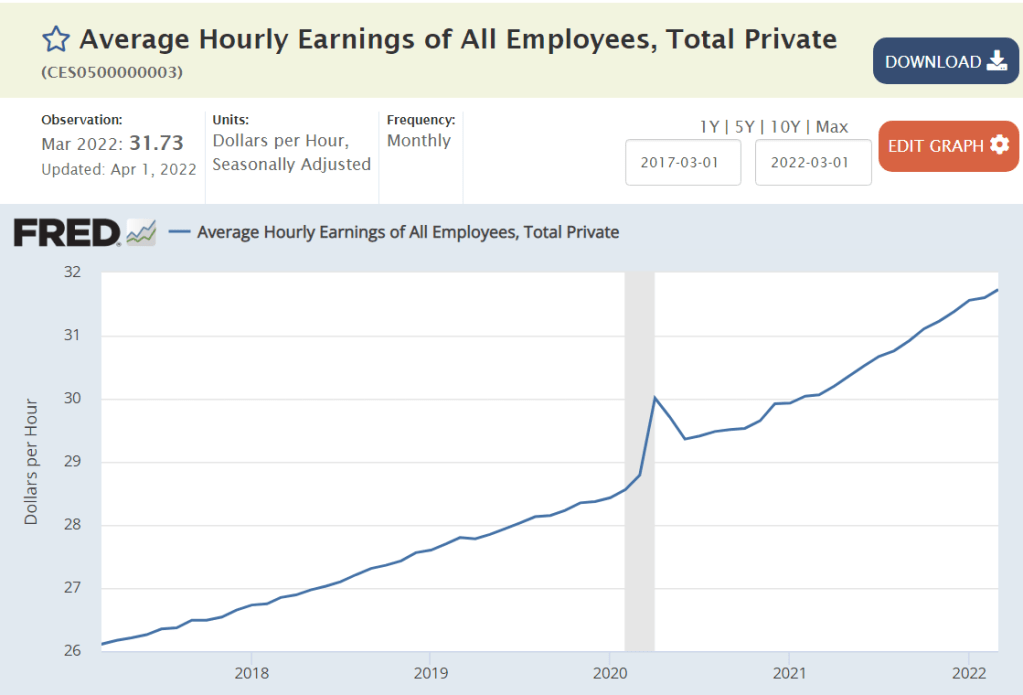

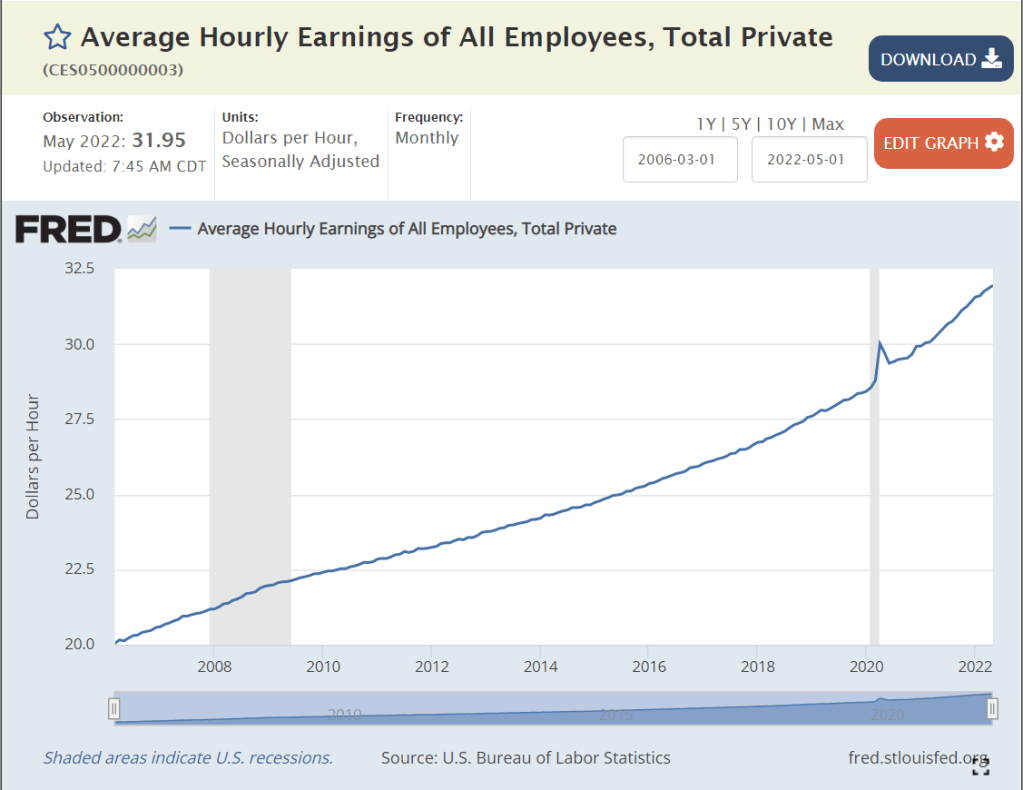

Average hourly wage up 12% to record $31.95.

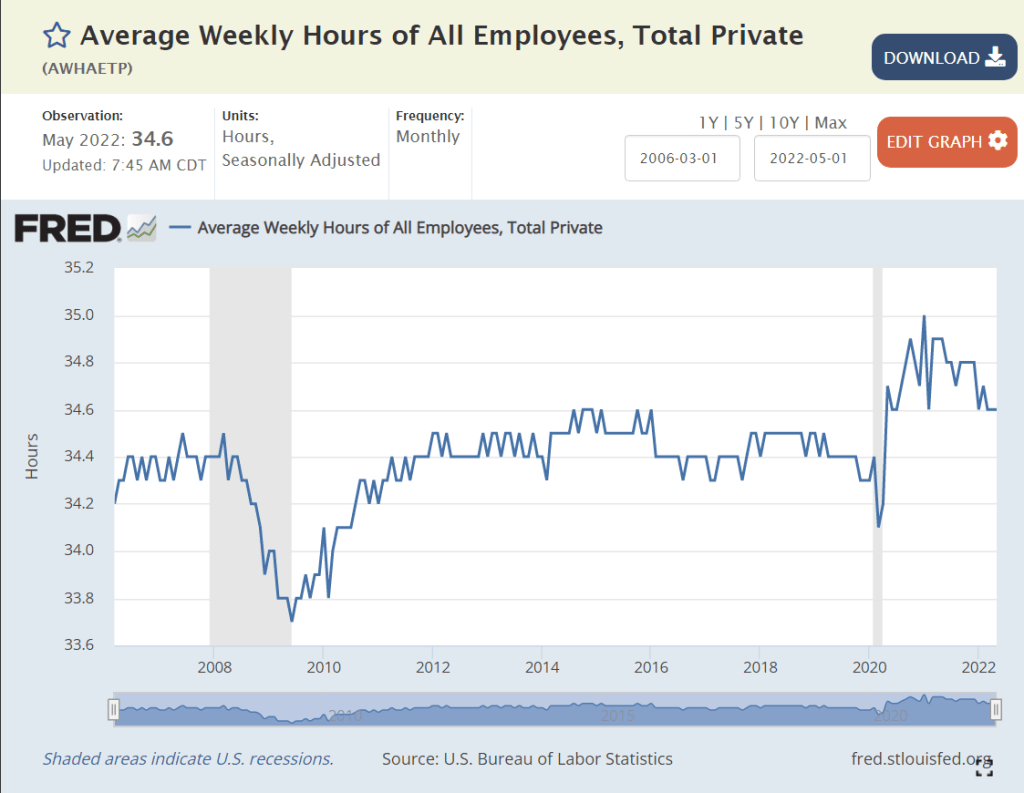

Hours worked is slightly higher than before the pandemic.

Record high 2.9% versus pre-pandemic record of 2.3%.

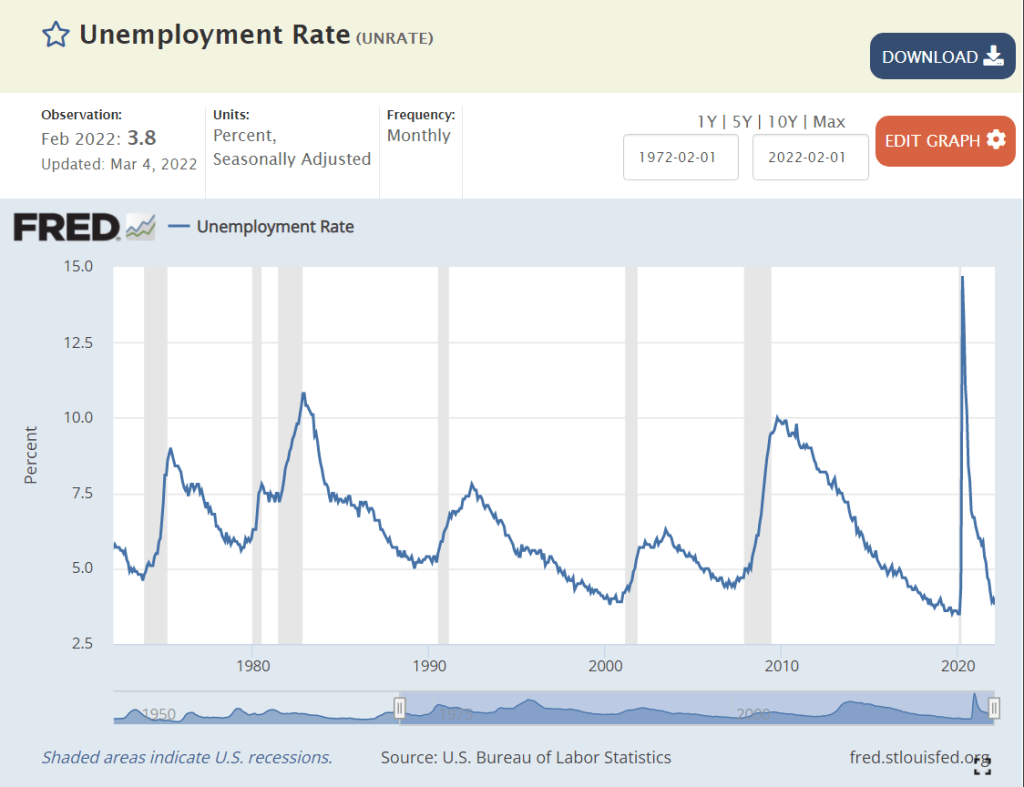

Unemployment rate is 3.6%, just above pre-pandemic 3.5%. Prior 3.5% rate was in 1969. This is the best in 50 years.

Underemployment rate at 7.1% is just above 7.0% pre-pandemic level. Underemployment rate was last this low in 2000.

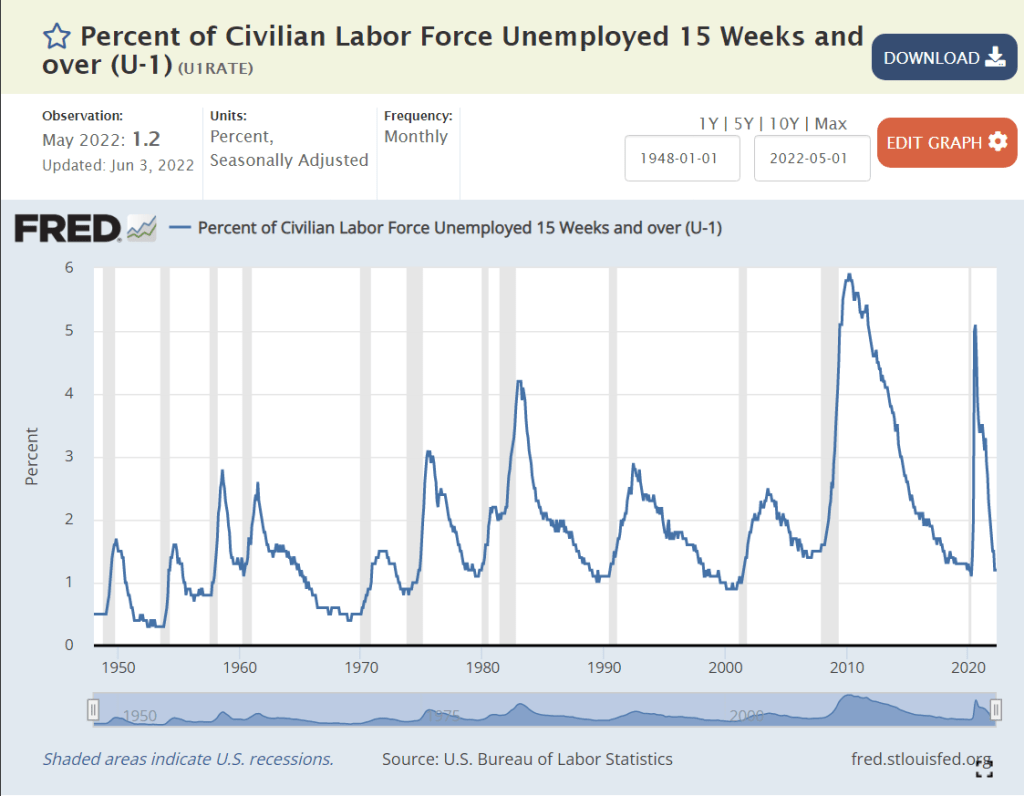

Long-term unemployment is at 1.2%, same as pre-pandemic level. The economy last delivered this positive level in 2000.

African-American unemployment rate is at a near-record 6% low. It was a little lower briefly before the pandemic.

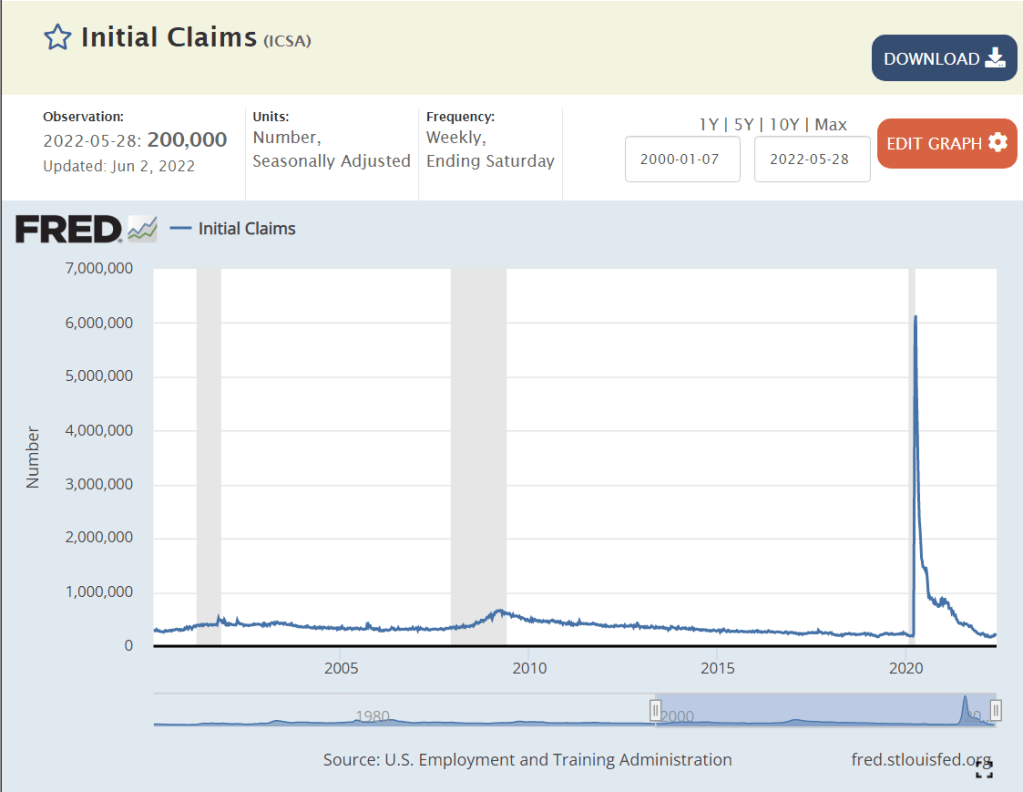

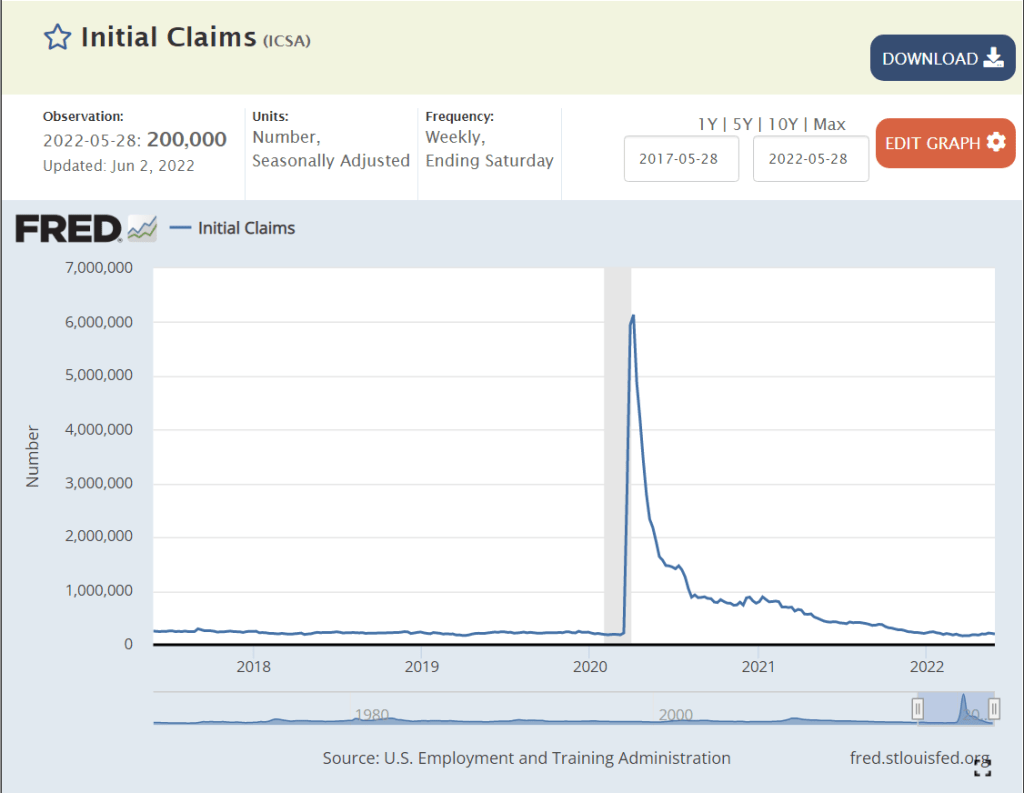

Initial unemployment claims reached the pre-pandemic low of 190,000 during 2022, but has increased slightly to 210,000. This compares with typical levels of 400,000 in recent decades.

Continued unemployment claims are at a 50-year record low of 1.3 million, down from the pre-pandemic level of 1.8M. 1.3M was last seen in 1969!

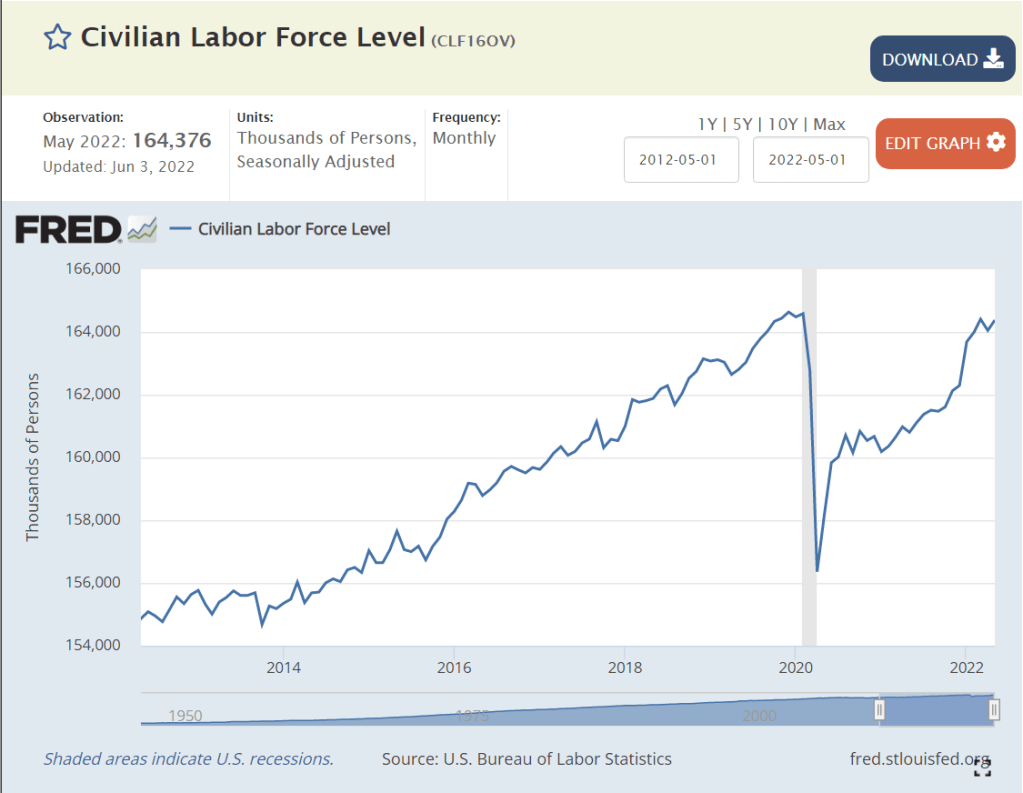

Civilian labor force at 164.4M is just below the all-time record of 164.6M.

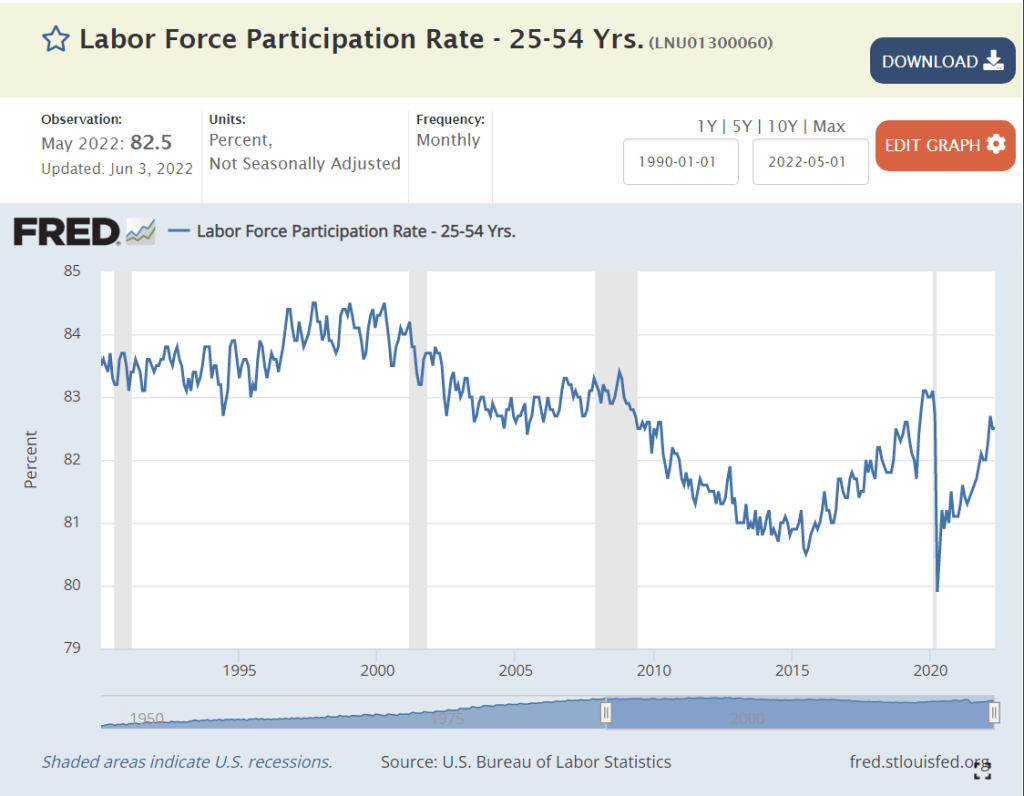

Prime age labor force participation rate fell from 84% to 81% by 2014. It recovered to 83% by the end of 2019. It has reached 82.5% so far in 2022.

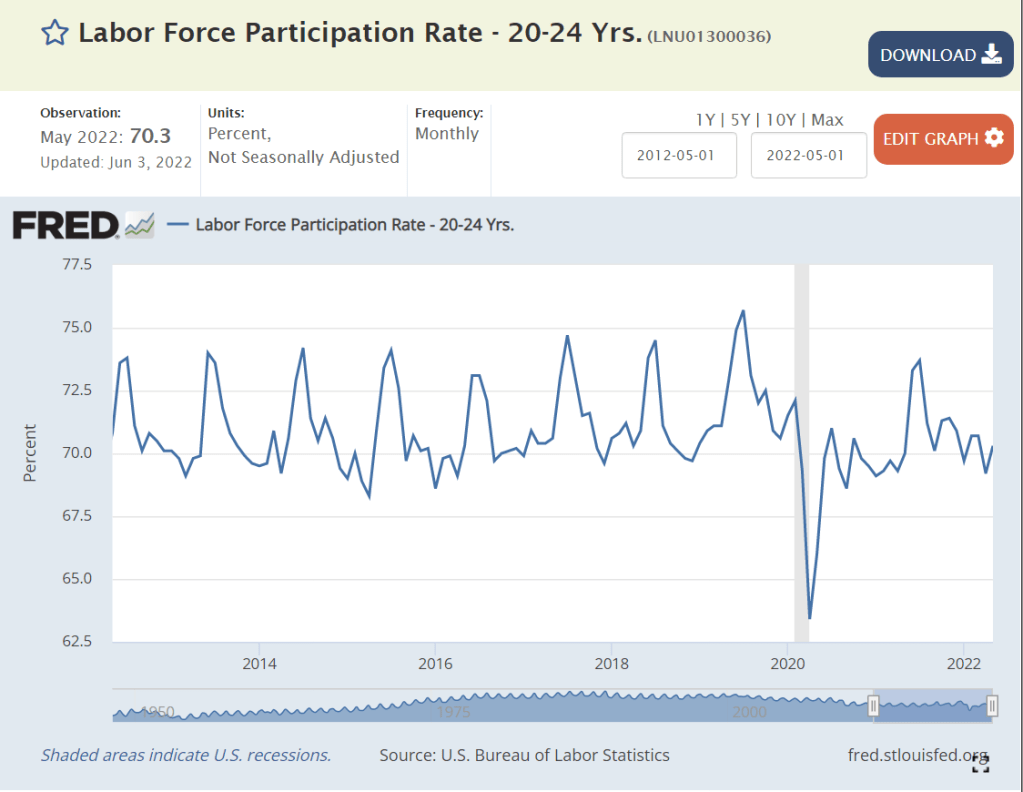

Teen labor force participation has slowly increased for a decade.

College age labor force participation has remained the same.

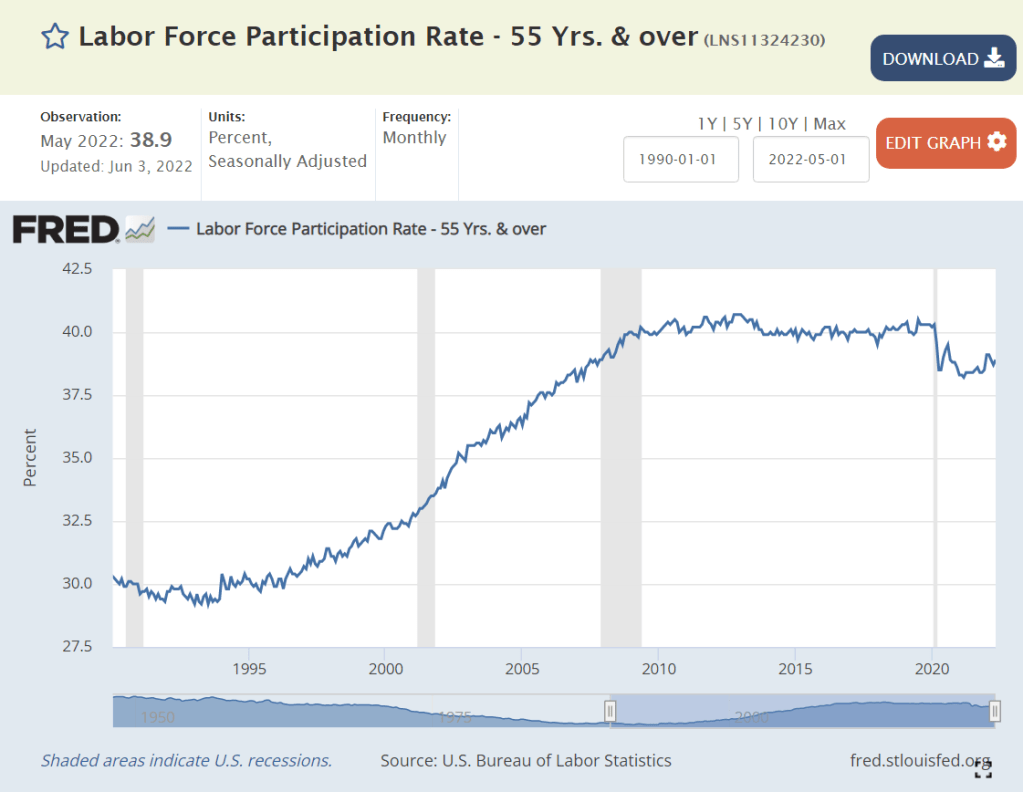

“Older” age labor force participation hit an all-time low of 29% in the early 1990’s, and then began to climb all the way to 41% in 2012. It remained at 40% throughout that decade. It dropped with the pandemic and has since recovered to 39%.

Female labor force participation continued its long climb to a peak of 60% in the late 1990’s. It dropped below 57% by 2014. It increased to 58% in the last 2 years of the decade. It has recovered to 57% after the pandemic.

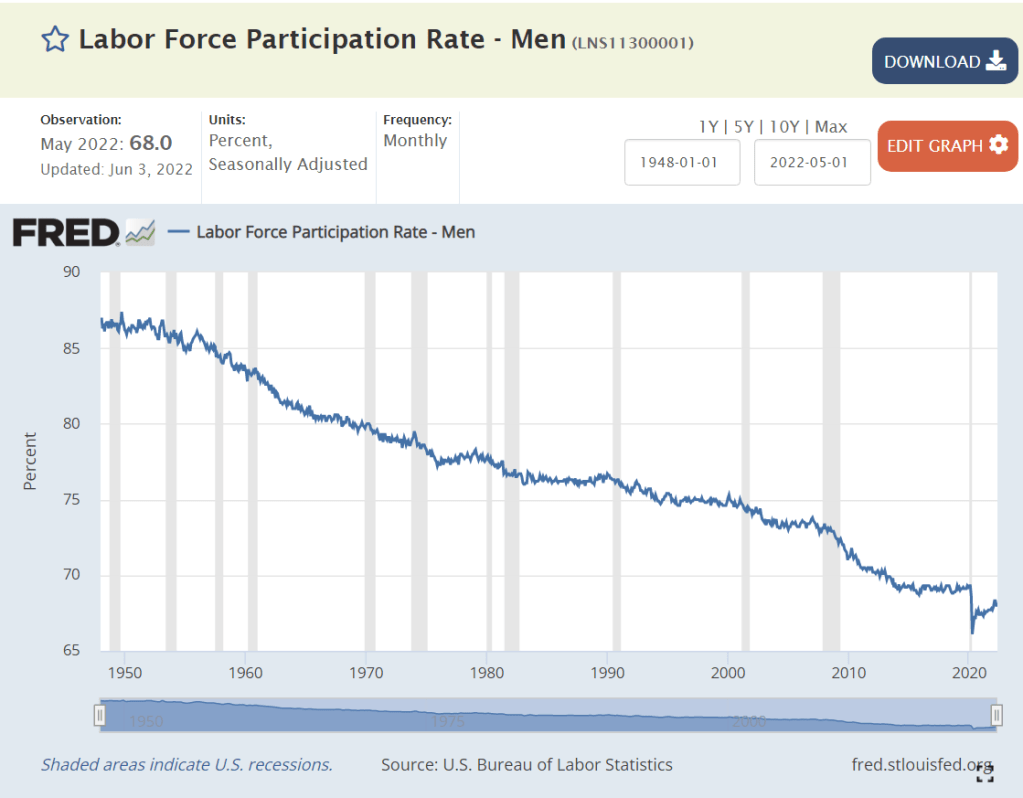

The male labor force participation rate has been declining for 70 years. It reached 69% in 2014 and remained there, without falling, throughout the decade. The rate dropped to 66% during the pandemic and has since recovered to 68%.

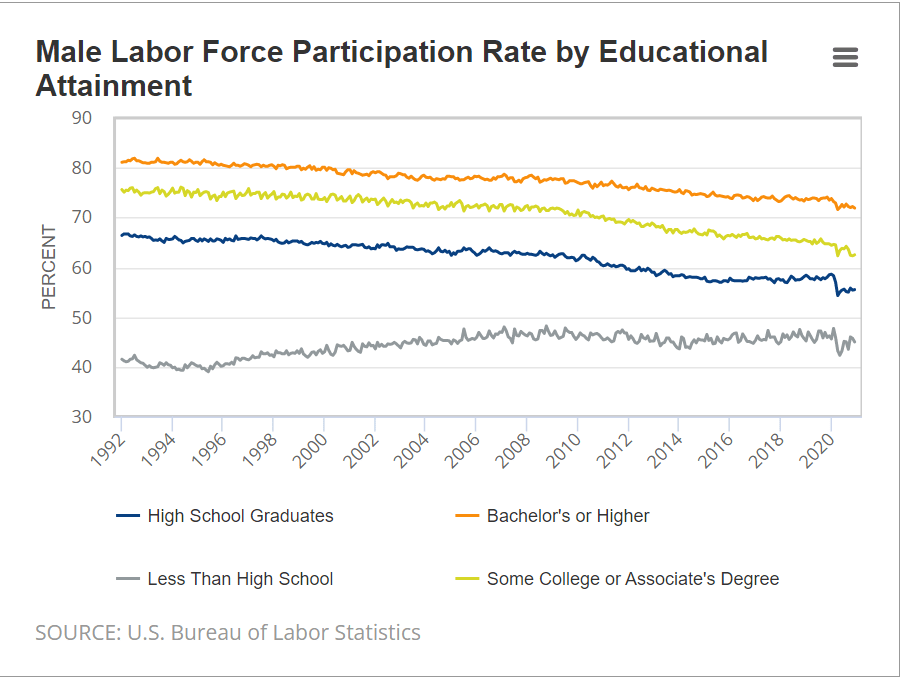

Labor force participation has declined by about 10% for HS grads, some college and college grad groups. Non-HS grads’ participation has actually increased. The similarity of participation changes by education and gender points to broader social factors playing a major role in these “economic” changes.

Summary

The measures of demand for labor are all at record levels. Unemployment rates are at long-term lows, just above the pre-pandemic levels which were driven by a decade long economic recovery. Labor force participation is down by 1% compared with pre-pandemic levels. Overall, this recovery from the pandemic challenges exceeds all expectations.