Available Positions

| Industry | 2007 Pos | 2019 Pos | 2022 Pos | Adds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Govt | 12.2 | 12.5 | 11.8 | -.4 |

| Other | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.6 | .2 |

| Construct | 7.7 | 7.5 | 7.6 | -.1 |

| Manufacturing | 14.2 | 12.8 | 12.7 | -1.5 |

| Mining | .7 | .7 | .6 | -.1 |

| Logistics | 5.0 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 1.9 |

| Education | 3.0 | 3.8 | 3.7 | .7 |

| Health | 15.3 | 20.3 | 20.4 | 5.1 |

| Leisure | 13.3 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 1.8 |

| State/Local Educn | 10.2 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 0 |

| Finance | 8.4 | 8.7 | 8.9 | .5 |

| Information | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.9 | -.1 |

| Profl Svcs | 17.8 | 20.9 | 21.8 | 4.0 |

| Retail | 15.7 | 15.6 | 15.8 | .1 |

| Wholesale | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.8 | -.1 |

| Total | 137.8 | 150.3 | 149.8 | 12.0 |

| Industry | 2007 Open | 2019 Open | 2022 Open | More Open |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government | .3 | .5 | .7 | .4 |

| Other | .2 | .2 | .4 | .3 |

| Construction | .2 | .3 | .4 | .2 |

| Manufacturing | .3 | .5 | .9 | .5 |

| Mining | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Logistics | .1 | .3 | .5 | .4 |

| Education | .1 | .1 | .2 | .1 |

| Health | .7 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| Leisure | .6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 |

| State/Local Ed | .1 | .2 | .3 | .2 |

| Finance | .3 | .4 | .5 | .2 |

| IT | .1 | .1 | .2 | .1 |

| Profl Svcs | .9 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| Retail | .5 | .9 | 1.1 | 0,6 |

| Wholesale | .2 | .2 | .3 | .1 |

| Total | 3.6 | 7.1 | 11.2 | 6.6 |

Open Positions as a Percent of Jobs Available

| Industry | 2007 Rate | 2019 Rate | 2022 Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Government | 2.4 | 3.6 | 5.4 |

| Other | 3.1 | 4.0 | 7.3 |

| Construction | 2.2 | 3.8 | 4.8 |

| Manufacturing | 2.3 | 3.4 | 6.4 |

| Mining | 2.1 | 3.8 | 5.6 |

| Logistics | 2.7 | 4.8 | 7.4 |

| Education Svcs | 2.4 | 2.9 | 4.9 |

| Health | 4.3 | 5.4 | 8.6 |

| Leisure | 4.3 | 5.7 | 9.8 |

| State/Local Ed | 1.3 | 2.0 | 3.2 |

| Finance | 3.5 | 4.2 | 5.4 |

| IT | 4.6 | 4.7 | 6.7 |

| Profl Svcs | 4.8 | 5.7 | 8.6 |

| Retail | 3.0 | 5.2 | 6.4 |

| Wholesale | 2.9 | 3.5 | 5.0 |

| Total | 3.3 | 4.5 | 7.0 |

Open Positions by Industry, 2021-22

The Department of Labor’s monthly survey provides various measures by industry. I’ve broken down the data into 15 industry segments. Eight (8) of these segments account for 5/6ths of all positions and I’ll focus on these 8.

The number of open jobs in the last year, July, 2021 – July 2022, is lead by Professional Services (2.0), Health (1.9), Leisure (1.6), Retail (1.1), Manufacturing (0.9), Government (0.7), Logistics (0.5) and Finance (0.5).

Seven industries accounted for 5/6ths of the increase from 4.6M openings in 2006-7 to 11.2M open jobs today. Health (1.2), Profl Svcs (1.2), Leisure (1.0), Retail (0.6), Manufacturing (0.5), Government (0.4) and Logistics (0.4) are the open job gainers.

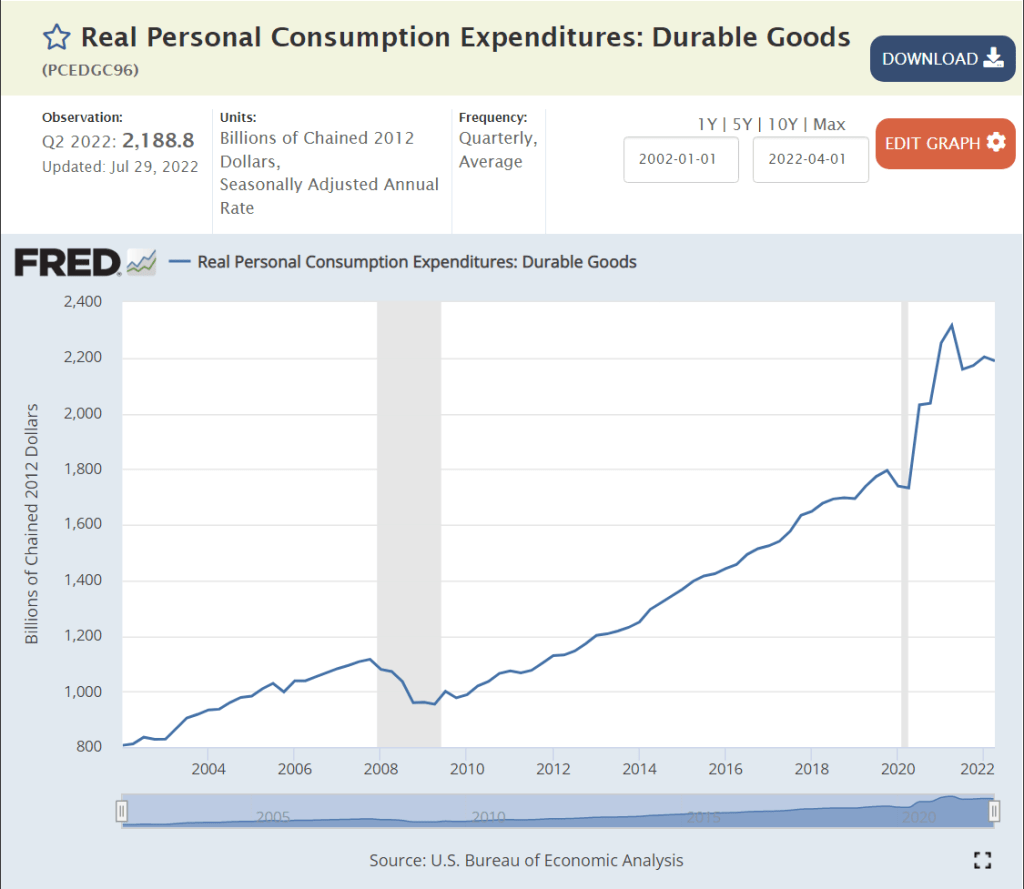

The pre-pandemic increase averaged 40% of the total 15-year increase for most industries. The Manufacturing industry showed job declines between 2006 and before the Pandemic, so 80% of it’s openings increase has been since the pre-Pandemic peak. The Business and Professional Services industry has also grown faster since the Pandemic, with 68% of its job growth in recent years. The Retail industry shows an opposite pattern, with 60% of it’s job growth before the Pandemic and a relatively weaker 40% post-Pandemic (on-line sales growth impact).

Total Positions Available by Industry

Total positions increased by 12M, from 138M in 2006-7 to 150M in the last year. Just 4 industries account for all of the growth, lead by Health (5.1), Profl Svcs (4.0), Logistics (1.9) and Leisure/Hospitality (1.8). The migration from ag/extraction to manufacturing to pure services is accelerating.

Open Positions Rate by Industry

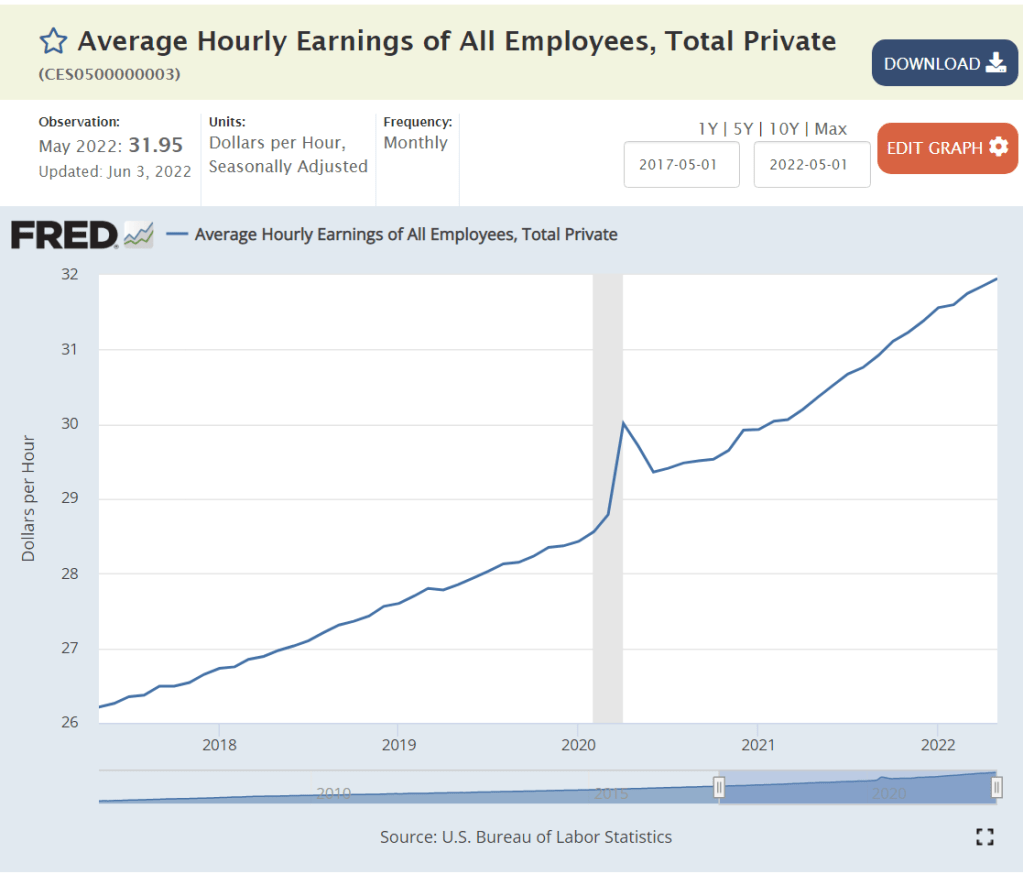

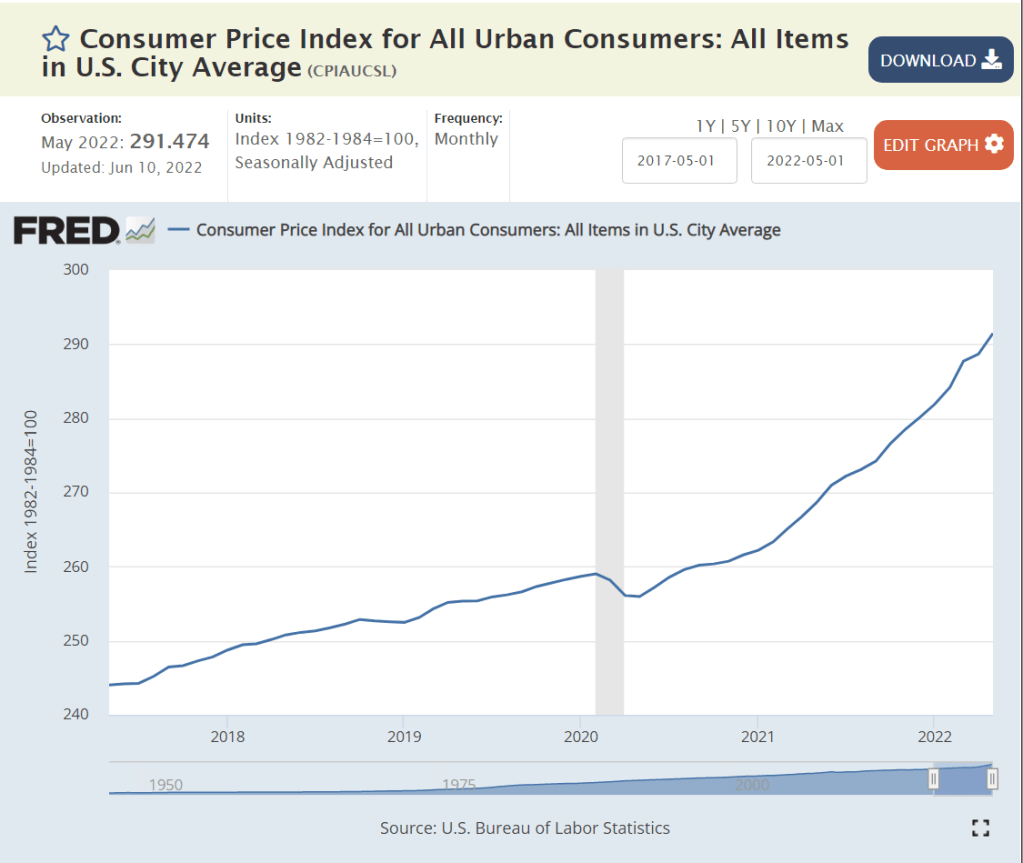

The open positions rate more than doubled, from 3.3% in 2006-7 to 4.5% in 2018-19 to 7.0% in the last year. Unfortunately, the larger and growing industry sectors have above average open position rates. Leisure and hospitality shows an incredible/unsustainable 9.8% job openings rate. Professional and business services and Health Care report nearly as high 8.6% vacancy rates. The Logistics industry has a higher than usual rate of 7.4% as it adds jobs at a faster rate in the home delivery era. The Retail and Manufacturing industries show elevated 6.4% open jobs rates. The Government and Finance industries exhibit 5.4% openings rates.

Changes in the Job Openings Rate

The overall job openings rate more than doubled from 2006-7 to the last year, from 3.3% to 7.0%. Keep in mind that 2006-7 was the peak of that business cycle with job openings at a cyclical low point. The Leisure and Hospitality industry had the largest increase, from its usually relatively high 4.3% to an “other worldly” 9.8%. The pandemic drove down travel and it has slowly recovered. The Logistics industry displayed the second highest increase, from 2.7% (it’s usual Manufacturing-like rate) to 7.4% as the Pandemic drove individual shipments to consumers. The Health Care industry continued its labor intensive growth, doubling from 4.3% to 8.6% of open positions. The Manufacturing industry evolved from its usual low 2.3% all the way up to 6.4% as labor demand in other industries grew and attracted its workers. The Professional and Business Services industry kept growing, resulting in a 3.8% increase in unfilled roles, from a typically high 4.8% to a very high 8.6%. The Retail and Government sectors had lower increases at 3%. The Finance sector had a lower than average 2% increase in open jobs.

Just a “Mix” Variance?

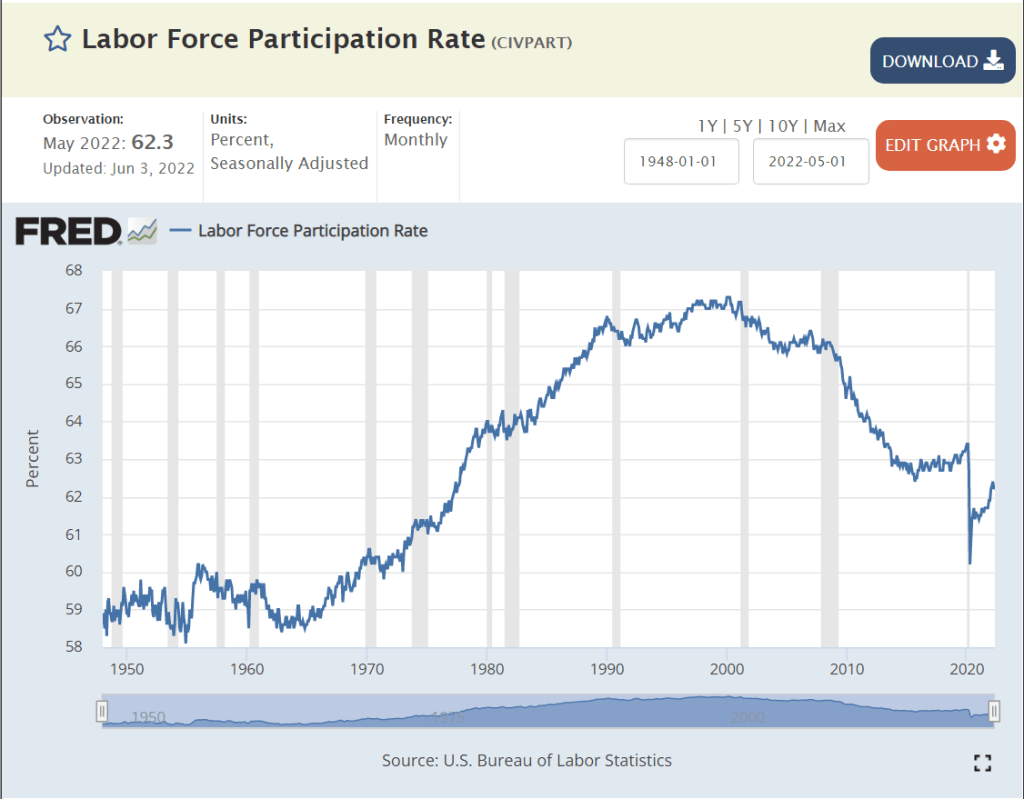

The US economy is very dynamic. Industries with low, medium and high job openings rates in 2006-7 each employed about 45M people. The low job openings rate industries (Govt, Manufacturing, Mining, and Educn Svcs) actually LOST 1.4M positions between 2007 and 2022. The middle rate of job openings industries (Logistics, finance, trade, other) added 2.6% net new jobs (1.7M). The high job openings rate industries (Health, Leisure, IT and Profl/Bus Svcs) added an incredible 10.8M jobs (22%)! The US has moved from agriculture to extractive to manufacturing to services employment. The personal and professional services industries are both the fastest growing and the most difficult to staff today.

What Happens During a Mild Recession?

Business and Professional Services openings drop by 3% of the total or 600K people. Health industry jobs decline by a smaller 1% as they are less sensitive to the business cycle, falling by 100K. Leisure and Hospitality are very understaffed and this is harming their growth. They might trim their employment by 2% or 300K positions. The Retail industry is in a long-run decline, so a 2% decline is likely, eliminating 300K jobs. Manufacturing is more cyclical than other industries, so its labor demand will fall more sharply, 3%, removing 400K job postings. The Government sector is somewhat buffered from recession pressures, so job openings might fall just 1% or 100K. Logistics firms are struggling to deliver, so a 2% job decline is the most I see, cutting another 100K positions. The Finance sector has been less volatile, so I estimate a 1% decline and 100K dip.. The remaining industries are likely to fall in tandem, requiring an additional 400K open jobs decline to meet budgets. This total 2.4M open position trim reduces the balance to 8.8M, far above the 7.1M pre-Pandemic level in 2018-19. I don’t think that the labor market will play its usual role in transmitting/amplifying negative finance, banking, housing, international trade, energy and other disruptions through the American economy.

Summary

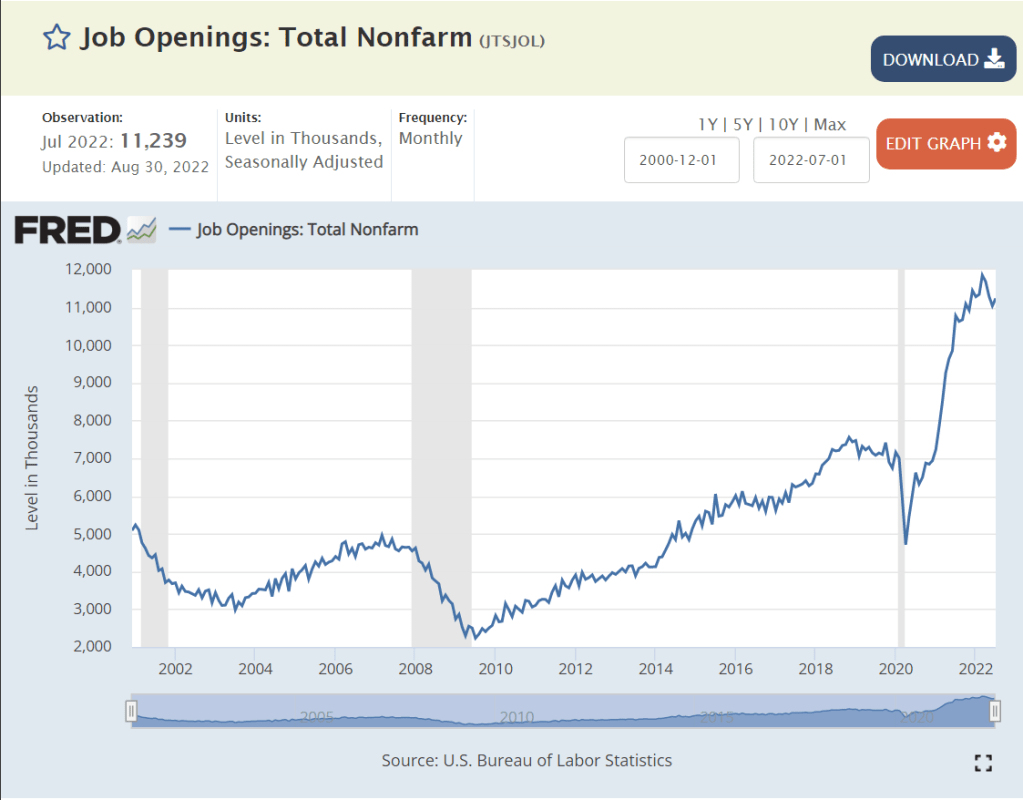

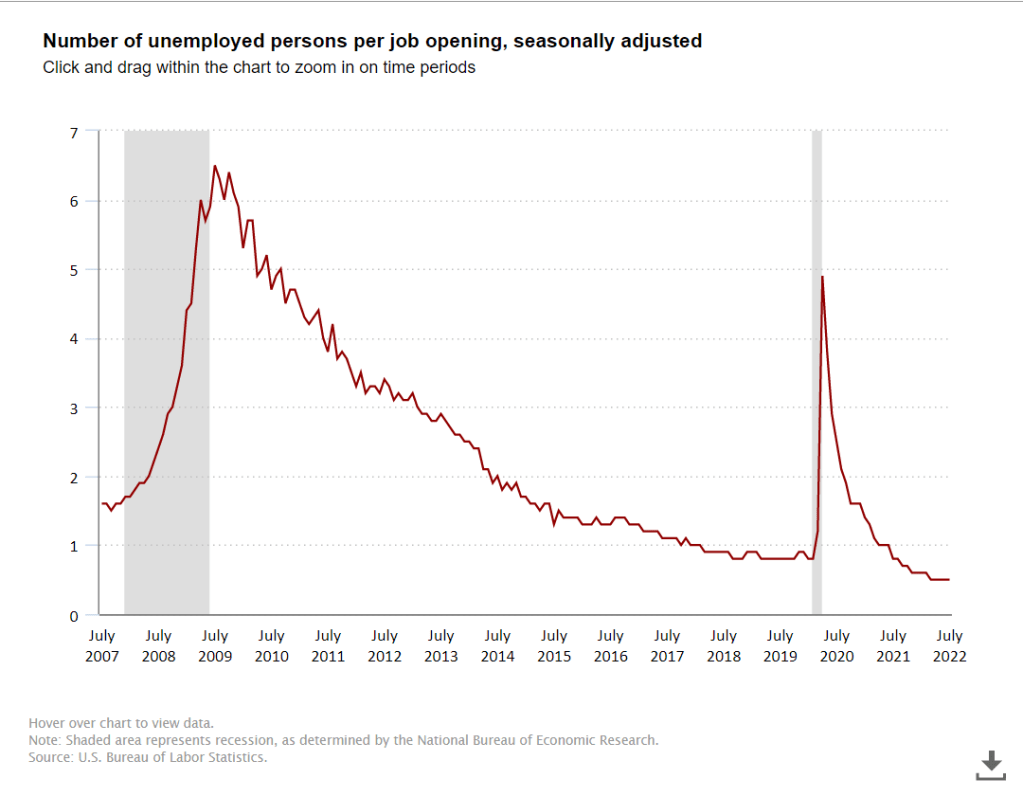

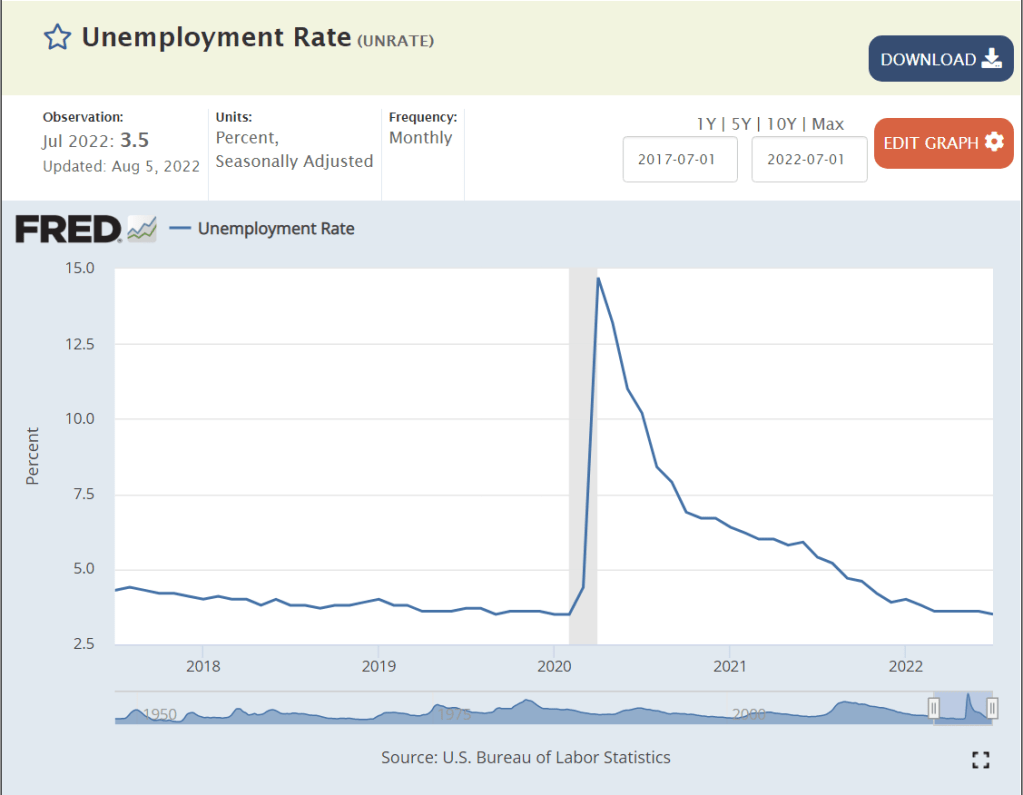

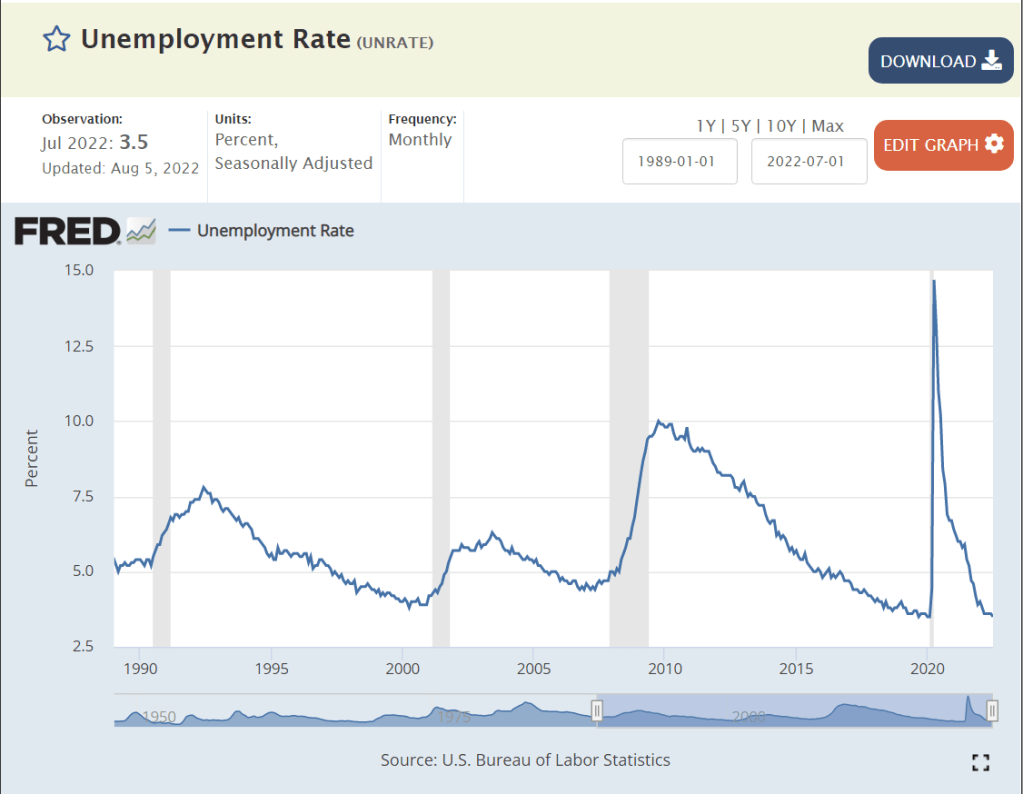

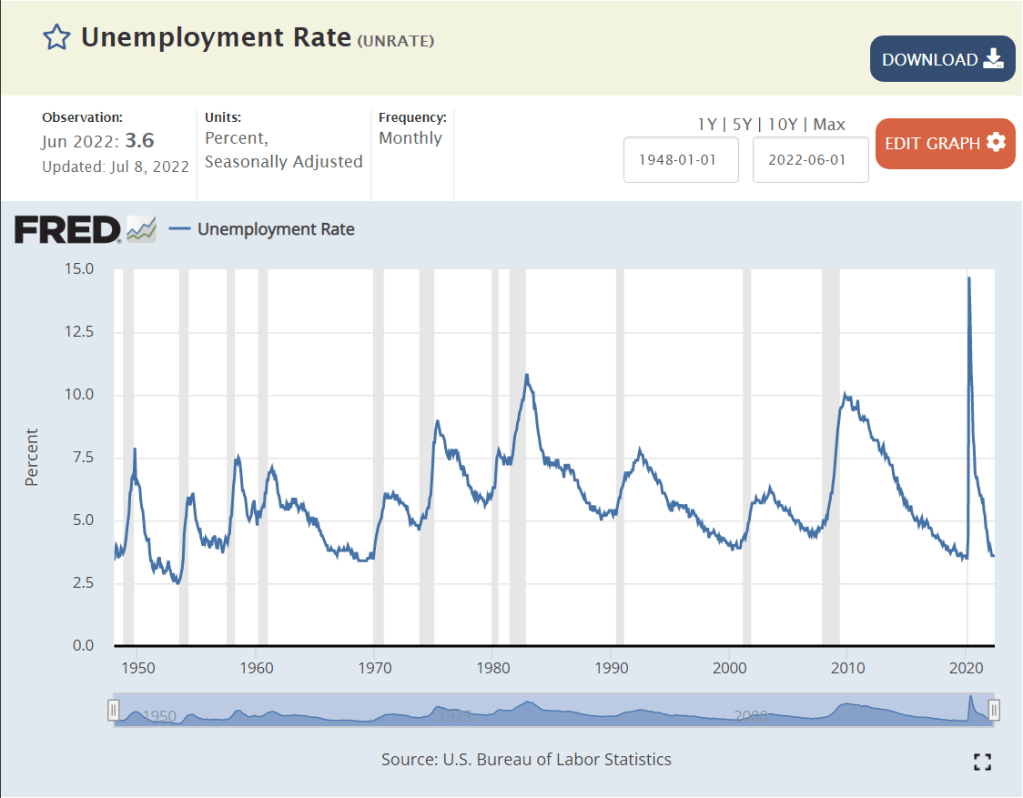

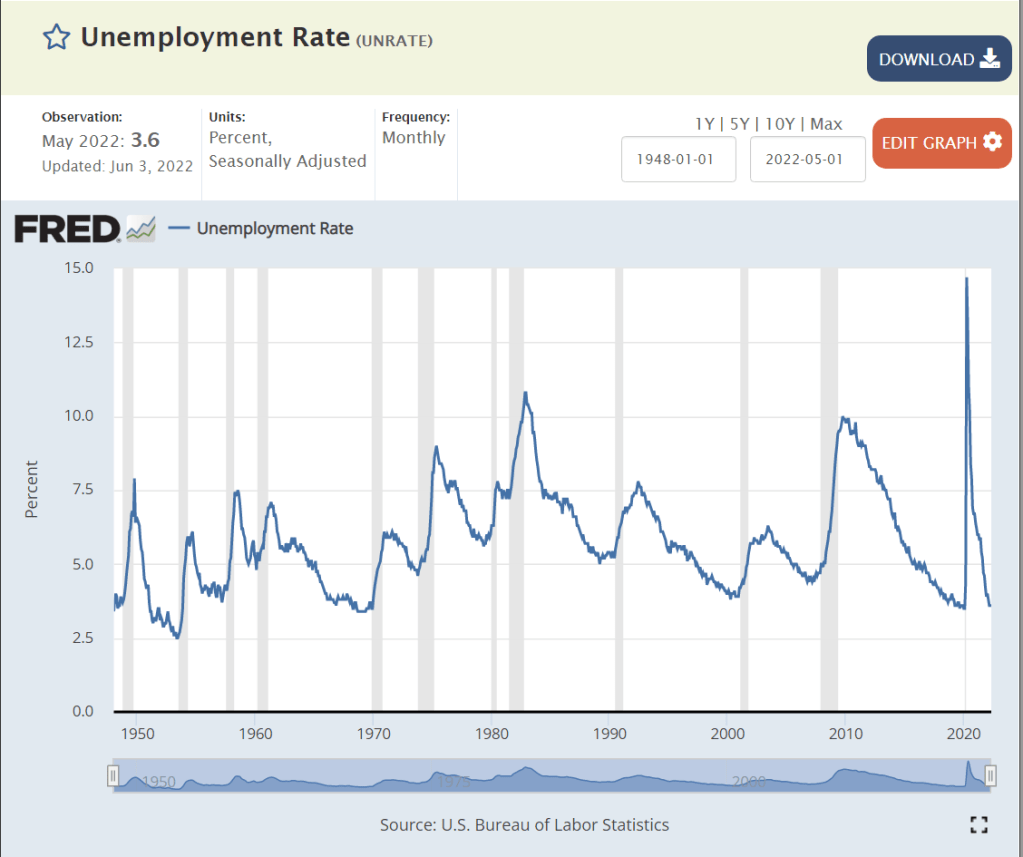

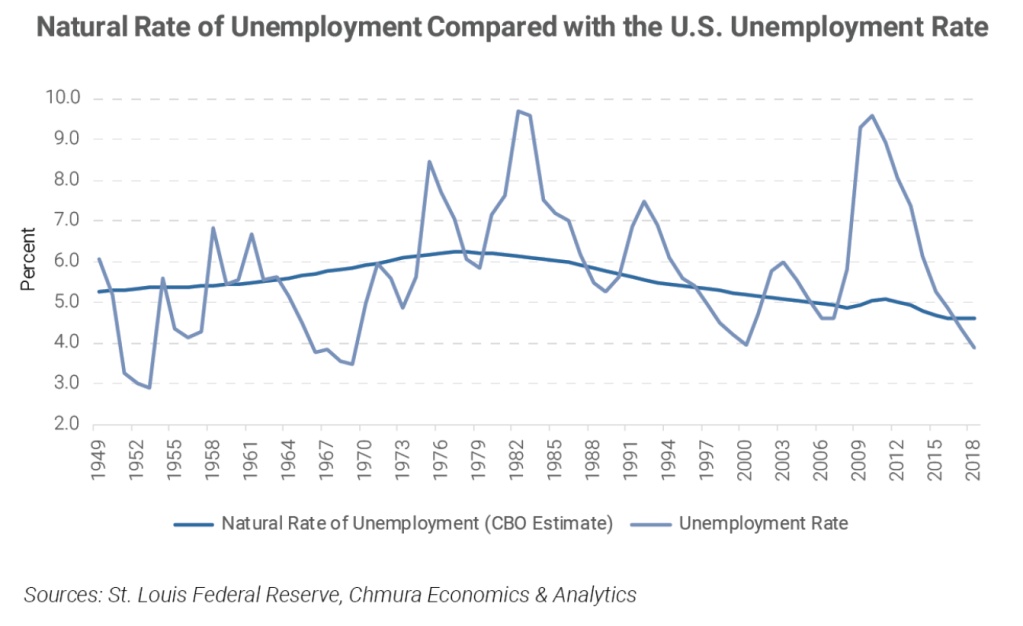

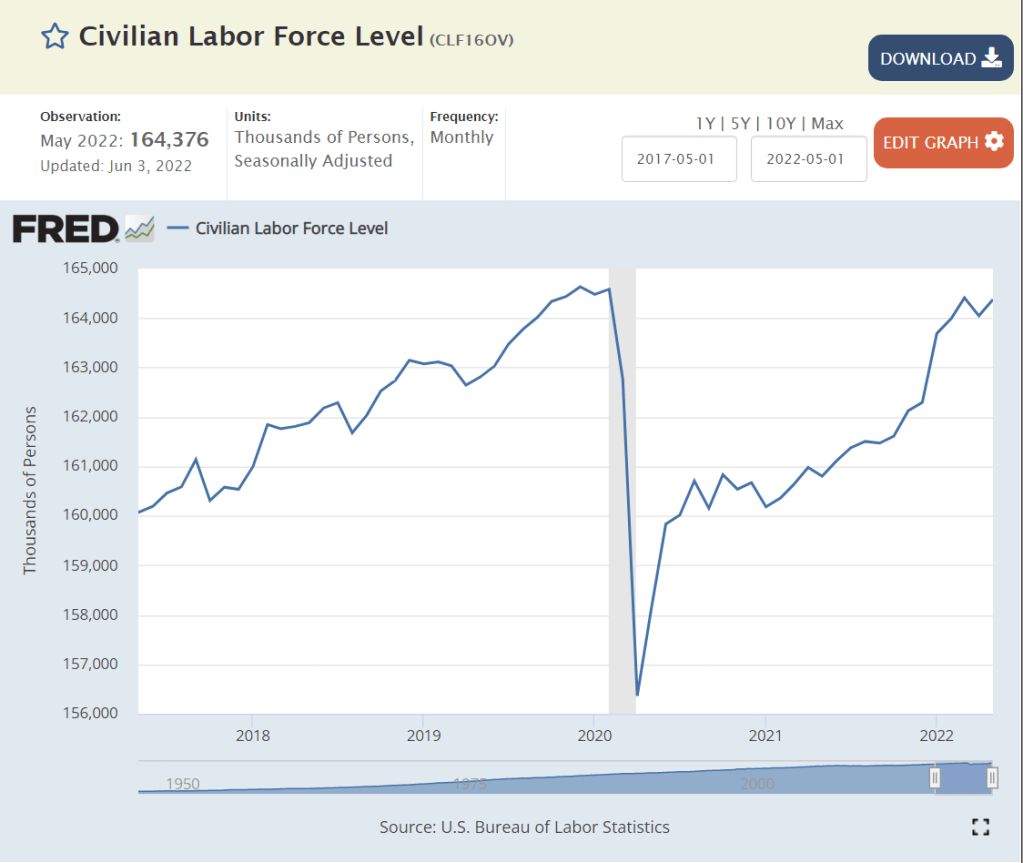

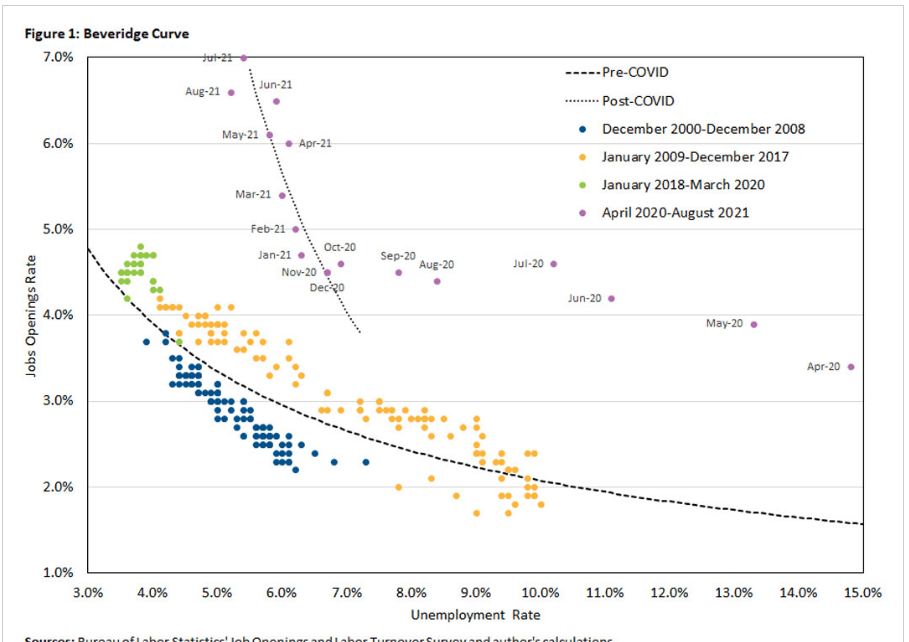

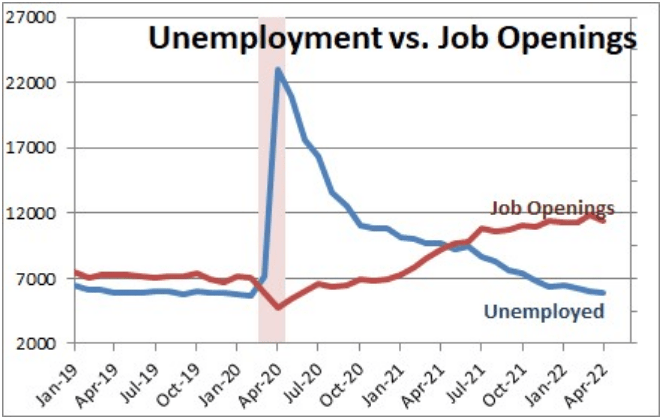

The US economy was at “full employment” in 2006-7 with just 4.6M unfilled positions. The extended recovery after the Great Recession delivered an even lower unemployment rate, but it also delivered a much increased 7.1M open positions. The post-Pandemic economy has returned to an amazing 3.5% unemployment rate, but the unfilled position count has climbed to a much higher 11.2M and stayed there. The current 7% vacancy rate is largely driven by 6 of the 15 industries with the highest rates: Leisure (9.8%), Health (8.6%), Profl Svcs (8.6%), Logistics (7.4%), Manufacturing (6.4%) and Retail (6.4%). American business is slowly learning to manage with a tight labor very market. Demand for labor should fall significantly in the future as firms employ greater technology, processes, capital goods and imports.

NOT.