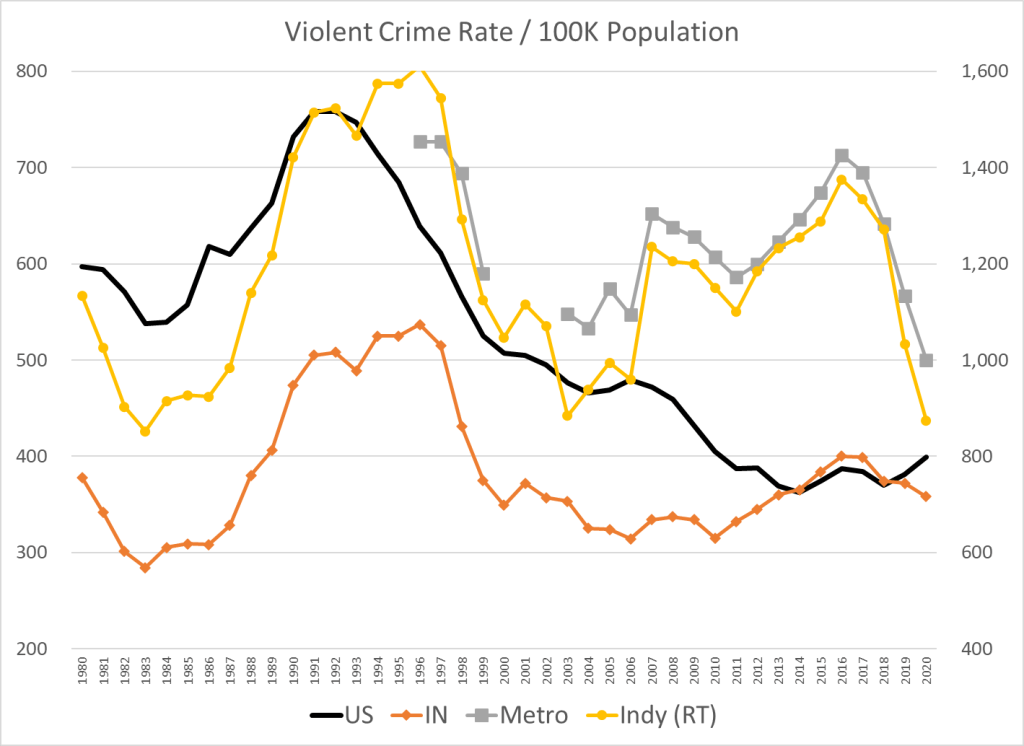

I’m using data from the FBI Unified Crime Reports. Total country violent crime increased by 25% from 600 events per 100,000 people in 1980 to 758 events in 1991 (thick black line). Violent crimes dropped dramatically to 500 events (33%) by 2001. There was a minor decline to 479 in the next 5 years and then another major decline to a minimum of 362 events, a 52% decline from the peak. Violent crime has increased to 399 in 2020, a 10% increase from the 4-decade minimum, but still 47% below the 1991 peak rate. In summary, the total country violent crime rate increased by 25% in the 1980’s, dropped by more than half in the next 25 years and has bumped back up to a level about one-half of the peak and one-third lower than the 1980 start. This is a quite positive result.

Indiana’s (orange line) general pattern mirrors the national figures. However, Indiana started at 378 violent events per 100K people in 1980, more than one-third lower than the national average. This is a quite significantly lower crime rate. Indiana’s violent crime rate increased by a larger 42% to a peak of 537 events in 1996. This was half again faster than the 27% increase for the country as a whole. Indiana was becoming more like the rest of the nation. Indiana’s violent crime rate dropped very quickly to just 349 events by 2000 (-35%), returning to 69% of the national level from 84% of the national level in 1996, a modest amount above the 63% ratio in 1980. Indiana violent crime inched down by 10% to 314 by 2010. The national crime rate was falling twice as fast, so Indiana was now at 78% of the average. In the “teens” decade, Indiana violent crime increased by 10%, returning to where it had been in 2000. National violent crime was flat during the “teens”, ending at 400 events. Indiana violent crime rate was essentially the same as the national rate during the “teens”, no longer one-third lower. It had returned to its starting point of roughly 400 events per year.

The city of Indianapolis (yellow line) is measured by the right hand scale, twice as high as the other 3 measures. Like most central cities, its violent crime rate is much higher than the national average. The Indianapolis crime chart follows the nation from 1980 through 2006. It starts at 1,134 events per 100K people, increases by 42% (like IN) to 1,611 in 1996, then drops by 45% to 884 events in 2003. The city’s violent crime rate is 1.9 times the national average at the beginning and the end of this 23-year period, but peaked at 2.5 times the average in 1996. The crime rate leapt up by 28% in 2007, reaching 2.6 times the national average. Violent crime in Indianapolis grew by 11% by the peak in 2016, 3.6 times the national average. The reported Indy crime rate has fallen by more than one-third in the last four years, ending at 2.2 times the national average. Looking at ten-year averages to smooth out the difficult to interpret variability, Indy has increased from 1.8 to 3.0 times the national average. The last 2 years look suspiciously low, just like 2007 looked suspiciously high. The 1,300 level for most of the last decade is more than 10% below the 1,500 peak level of the 1990’s. So … Indiananapolis violent crime is now down a little compared with the peak, up very significantly compared with the national average and roughly within the range of the first 30 years.

The Indy metro data follows the city of Indianapolis pattern very closely.

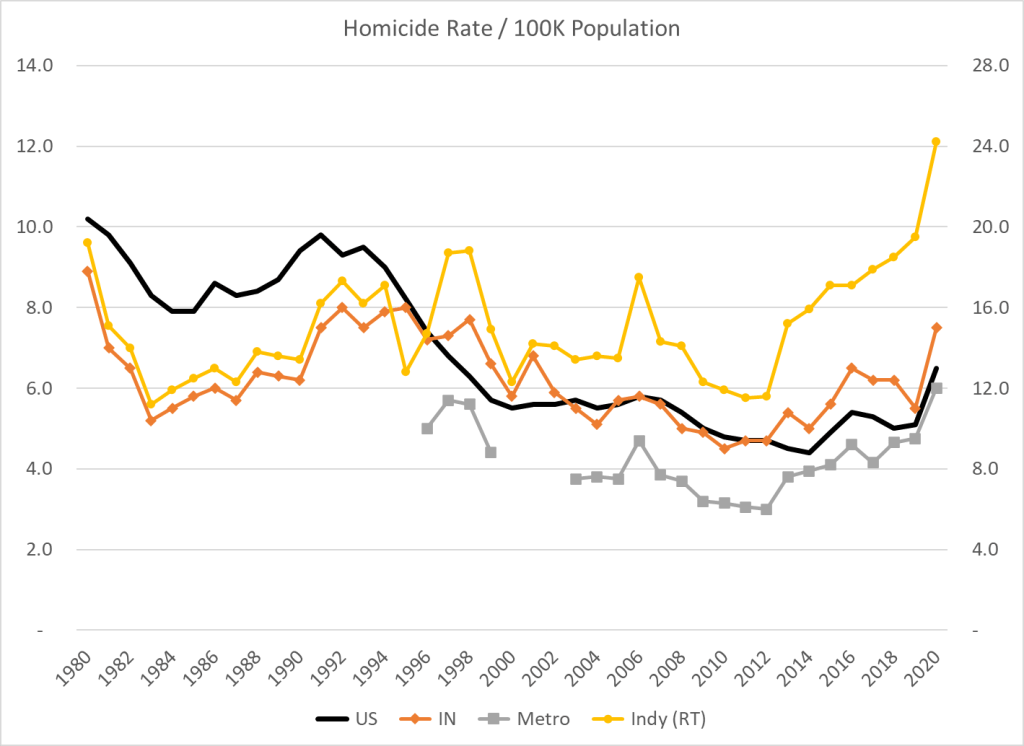

The national homicide rate per 100,000 people averaged 9 from 1980 to 1995. It dropped by one-third to just 6 by 2000 and stayed at that level through 2007. It declined to an average of just 5 for the next decade, before spiking up in 2020 (and 2021, FBI official data unavailable). The national homicide rate is up significantly, but one-third lower than in the eighties and early nineties.

Indiana started at an unusually high 9 homicides per 100,000 people in 1980, but averaged just 6 for most of the eighties, just two-thirds of the national level. Indiana homicides jumped quickly to a peak of 8.2 in 1992 and remained near 8 for six years. The national homicide rate fell rapidly from 10 to 6 during the nineties, leading to a six-year period (1997-2002) where Indiana homicide rates were slightly above the national average. Indiana homicide rates closely matched the national average for the next decade, falling to 5 in 2008. Indiana homicides increased by 50% between 2014 and 2020, from 5.0 to 7.5 while the national average increased about 50% from 4.4 to 6.5 events per 100K people. Indiana has averaged about 6 homicides per 100K people during this 4-decade period except for the 8 homicides rate in the mid-nineties. The most recent murder rate has returned to that peak level.

The city of Indianapolis very closely matches the Indiana pattern for the first two decades, with 12 homicides per 100K people in 2000, about double the national average of 6. The Indy rate pops back up to 14.2 in 2001 versus the 5.6 rate for the country (2.5 times higher). Indy follows the slow national decline through 2012 to 11.6 events versus the 4.7 country level (2.5X). Indy’s murder rate jumped 31% to 15.2 in 2013, and has climbed steeply since then. It reached 19.5 in 2019, a two-thirds increase in 7 years. It jumped again in 2020 to 24.2 and is estimated to be more than 28 in 2021. Indy averaged about 14 murders per 100,000 people in the first 32 years of this period. 2019 was a 40% increase. 2020 was a 73% increase. 2021 is a doubling.

The Indy metro area pattern follows the city of Indianapolis. Metro Indy’s homicide rate averaged 1.35 times the national rate from 2003-2011. It has averaged 1.76 times the national average from 2012 to 2020.

Summary

Indianapolis has a huge violence and murder problem. Period. Violence at the national level is way down. Murders at the national level are much lower than the peak period. Indianapolis’ violence rate shot up in 2007 and only declined in the past 2 years. Indianapolis’ murder rate shot up in 2013 and has continued to climb. I try to highlight the “good news”. I emphasize long-term data to provide context. I try to minimize/offset the sirens of local and national journalists. But, for this topic, there is no apparent “silver lining” or “on the other hand” conclusion.

https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/ucr/publications

https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/1999

https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/us/in/indianapolis/crime-rate-statistics

https://www.disastercenter.com/crime/incrime.htm

https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/explorer/crime/crime-trend

https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019

https://www.themarshallproject.org/2016/08/18/crime-in-context

https://abcnews.go.com/US/12-major-us-cities-top-annual-homicide-records/story?id=81466453

https://www.wrtv.com/news/local-news/crime/2022-indianapolis-homicide-map

https://www.wrtv.com/news/local-news/crime/indianapolis-had-271-homicides-in-record-breaking-2021

https://fox59.com/news/indycrime/crime-mapping-neighborhoods-impacted-the-most-by-homicides-in-2021/

https://www.wfyi.org/news/articles/law-enforcement-community-work-to-solve-more-homicides