Lots of press on the topic of a “new” labor market. Some of the experience seems to be genuinely new, some of the situation seems to be our old favorites, supply and demand.

Derek Thomson’s recent Atlantic article is a good one,

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/10/great-resignation-accelerating/620382/

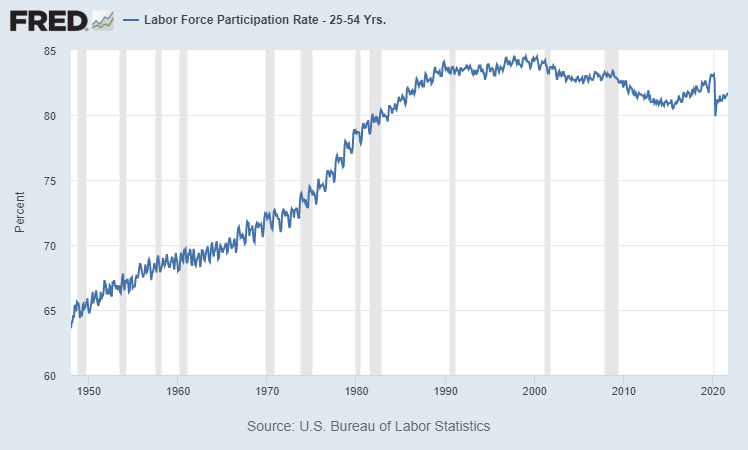

On the supply side, labor force participation is the big driver.

Focus on the core 25-54 age group to avoid the impact of various “mix variances” with changing enrollment rates and different retirement patterns. HUGE increase from 1950 to 1990, 65% to 84%, as women joined the US workforce across 4 decades. The rate stayed roughly constant for 2 more decades, through 2010, falling back a little to 83% in the late 2010’s.

Since 2006, we’ve had some modest changes. The rate fell from the relatively stable 83% rate through 2009 down to 81% in 2012. The recession knocked 2% of the population out of the workforce. For the next 4 years, through 2016, the participation rate remained at 81%. This is a variable that does not change quickly. People make long-term decisions, knowing that re-entering the work force requires very significant “effort”, investments, networking and accepting lower wages versus history. By the middle of 2016, almost 8 years after the decline that started in early 2009, the participation rate started to increase again. Note the many articles about the “jobless recovery” during W Bush’s time and Obama’s first term. The labor markets are not quite as responsive as desired. In the next 4 years, the participation rate returned to its prior level. That’s an increase of 0.5% per year during a prolonged economic boom period. Again, this measure of available supply does not change rapidly in normal times.

The pandemic dropped participation back to 81% in a short few months! In the last year, the participation rate has risen by a little more than 0.5% to 81.7%. We can expect to see this same kind of improvement for each of the next 3 years based upon recent history. But, even with all of the measures of underemployment and open positions, it is unlikely that the labor market will attract new employees faster than this rate.

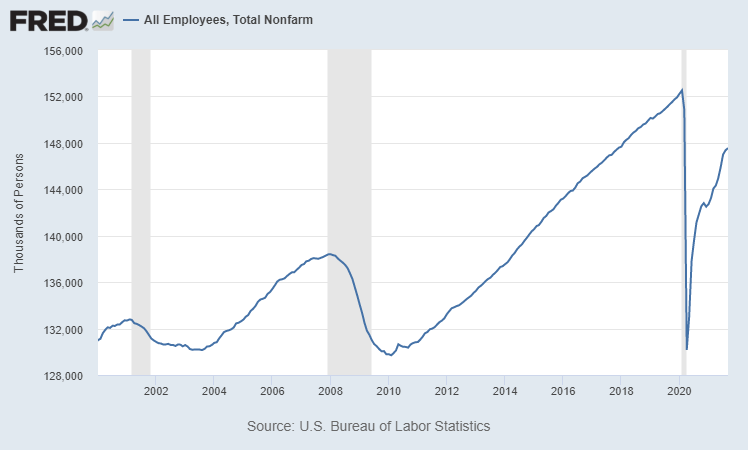

The number of nonfarm workers employed reflects the results of labor markets. This is another measure that typically changes slowly.

The number of US employees stayed relatively flat from 2000-2004. The W Bush (jobless) recovery DID add 6 million workers. The “Great Recession” dropped the headcount by 8 million, back down to the 130 million level of the prior recession. Note that we had 11 years with essentially ZERO net job growth.

The economy found its footing in 2010 and we had 9 years or growth, adding 22 million employees, a truly remarkable period of prosperity. This recovery is remarkable for the steady pace of job growth, a constant 2.4 million per year.

By the end of the 2020 pandemic year, employment was down to 143 million, a decline of 9 million. This is similar in size to the “Great Recession’s” 8 million job loss. In the last year, the economy has added 5 million jobs, a pace TWICE the level of the prior recovery. We may be slowing down, or the job adds may continue between the 2.4 – 5 million annual rate. This is VERY GOOD news.

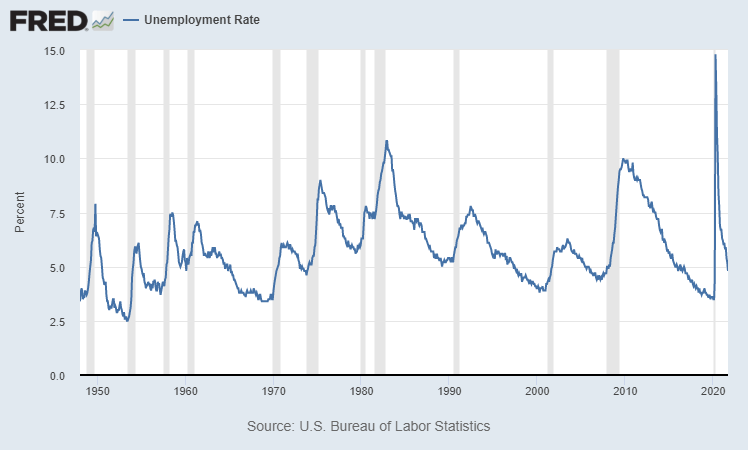

In the long-run, the US economy struggles to reduce and hold unemployment below 5%.

In the post-WW II boom times, 4% was reached several times, but thereafter quickly increased back above 5%. The “stagflation” era of the 1970’s indicated that “full employment” might be as high as 6%. The boom periods of the late 1990’s and 2000’s drove actual unemployment below the presumed 5% unemployment rate, but always just briefly. The long and smooth 2010’s recovery broke the rules. Unemployment rates fell and fell down to an unexpected 3.5%.

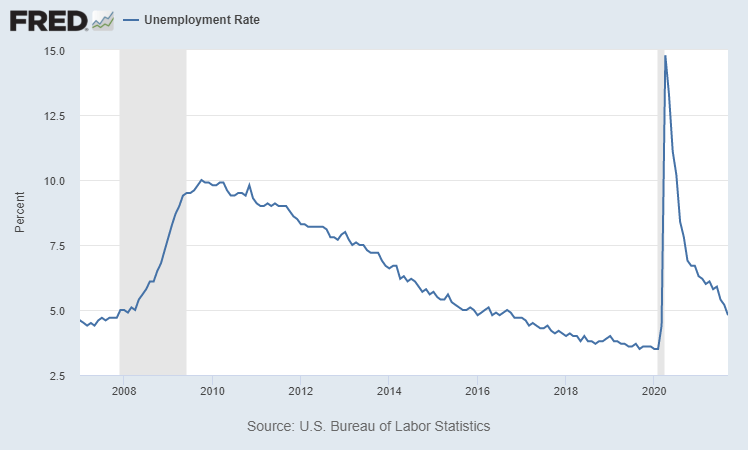

By the end of 2020, the unemployment rate had dropped to a more reasonable 6.7% from the measured peak of 15%.

It has recovered by a very strong and quick 2% in the last year, reaching 4.8%. This is near the long-term level of “full employment”, where demanders must provide increasingly attractive offers to entice supply.

This recent disconnect between supply and demand is seen in the unusually high job openings rate.

From 2000-2014, the economy averaged a 3% rate of job openings to labor market participants. About 1 in 30 or 33 jobs were “open”. The “Great Recession” drove this ratio as low as 2%, with just 1/50 jobs open. Following the “Great Recession” this ratio of job market demand increased for a full decade, from 2% to 4.5%, where only 1 in 22 jobs were open. Note that this is more than twice as many as in the depths of the “Great Recession”.

The job openings rate snapped back to the recent 4.5% level in the second half of 2020. It has since grown to a record 7%, or 1 in 14 positions unfilled. This is a “loose” labor market of historic proportions. Demand is clearly exceeding the slow response of supply in the labor force participation rate.

The “quits” rate has attracted the most media attention as it is even more extreme.

The voluntary quits rate averaged 2% from 2001-2008, 1 in 50 workers. It dropped to just 1.5% (1/66) during the Great Recession. It slowly increased with the recovery to 2.3% in the heady days of 2018-19 (1/44). The quit rate returned to its recent level very quickly by July, 2020. It has since increased to 2.8% or 1 in 36 workers each month. On an annual basis, this is 1 in 3 workers voluntarily leaving their employment!

As we’ve seen with the supply chain bottlenecks, the labor market is currently unable to recover quickly enough.

The economy did employ 152 million workers before the pandemic. We need 4 million more to reach that level. Based on recent history, this is an achievable level, but it will require 18 months or more to achieve.

In the mean time, employers will raise wages and provide more flexible terms to attract marginal workers back into employment.

As the “great resignation” pundits say, the pandemic experience changed the expectations of potential employees. They have found that they can “survive” rather than accept low wage positions with poor work conditions. This will change their behavior for years to come.

[…] The Great Resignation: Labor Markets Run Amuck […]